Summer is a kind of suffering. The heat, for one, grows hotter every year. The skies get smokier. The rivers drier. One of the great cruelties of change is the decaying promise of what used to be. How it lingers in the air, this feeling, this expectation that things could somehow be carefree.

But there's something delicious in that. Hugging a cold bottled gallon of water in my bed as a partner to keep me company. The fan on my skin. It is so nice, in a way, to no longer be buzzing with the noise of mundane world-worry that settles in cooler moments. There's no room for trivialities here; even an average afternoon can just feel like survival. And there is an accomplishment in that — to live through the plodding pace of another hot day.

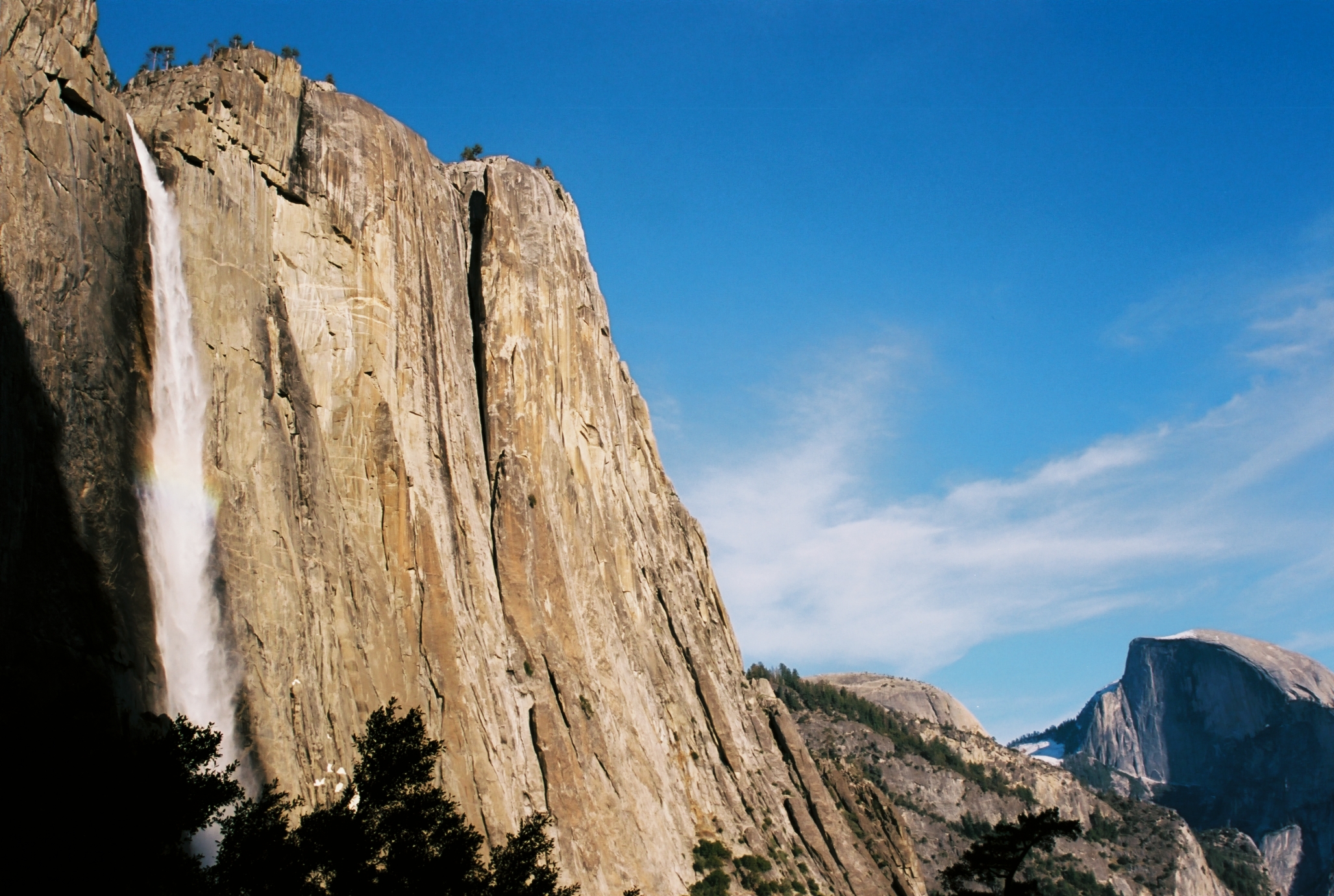

I love to chase feelings and sensations, even these kinds. Summer, thankfully, provides sensations in abundance. The world is shining with sounds; the hum of fans, the kick of the blanket off skin. Simple sonics strike with new presence. I often feel a little zany and unsettled in the summer. Particularly in the desert, where I find myself undercut by mysterious irritations and woes that ultimately seem to find their root in dehydration and troubled sleep. Everything is intense. My fantasies float to higher elevations, to pine trees and lakes, to thirty to sixty degrees fewer of temperature. Gas prices sometimes rise to meet these fantasies and pop them as balloons.

As a young teen I craved the summer suffering on some level. There was a 13-year-old summer where I felt lovelorn, lonesome, and languid. On a family reunion trip held in Sacramento, I took a moment to walk alone, to be alone with my thoughts. It was in an open-air mall. The heat was in the hundreds. This was one of my first memories of vivid heat, all-encompassing, a hot humid breath that swallows you in the mouth of the world. And I felt small in the mall, its echoes of big sound, laughter splashing across the room, footstep staccatos intermixed with pop music and loud signage.

I was crushing hard on a classmate at the time, and the feelings were not mutual. So I felt distant and wished things were different. I was longing, longing, longing. The heat felt intense and oppressive and I kind of wanted to die. But I felt it all: my big, booming, battered heart, the hissing of insects, the sauna of summer all around me. In some ways in this onset of pubescent feelings I felt like I was feeling my body for the first time. And I hated it. And I loved it.

For me summer will always have a mix of these feelings, of being so wholly alive and yet so yearning and deadened by what goes unfulfilled. Summer can be a cackle, can be a mockery. Summer can be a temptation or a torment. Summer strips us all, exposes us. The beach, the lakeshore, the outing. All become subtly competitive. All across the beach, the trail, the gym, there are bodies and minds who wonder and worry about how they are seen, alongside other kinds of suffering in the sweltering haze. There are industries and billboards and pressures weighing on folks to meet the occasion, to be seen once and for all. And there are those who shelter indoors, blinds down, Netflix on, hiding from the world; or suffering out of doors, no walls to protect, starved, splayed on the sidewalk, overlooked, neglected. Few are at ease.

Where I grew up, along the coast, summers started solemnly. In many ways, summer was the saddest season. Summer rolled in with May Gray and June Gloom. Entire communities became entrenched in a deep fog for hours, weeks, months on end. Sunlight would shine for a few fleeting moments then be blinked out behind the mournful blur. I found it tough to get through. The mockery of summer seemed doubly so growing up in sunny Santa Barbara, a pristine picture of a place. Like much of westernized California, Santa Barbara was built on the concept of summer. At the solstice height, the longest days of the year were plunged into the gloom, and it seemed to me even then there was something suspect about the promise of 'summer.'

Summer is a postcard of the past. Even when it was more pleasant it was the season of bygone eras and cherished childhood experiences. America itself is built on monuments to nostalgia and cathedrals of kitsch. The whole of the distilled image of the 1950s seems to market life as a perpetual holiday. From the sidewalk-searing shadows of the atom bombs came the images of Christian roadtrips through America's great national parks. We've been coping and chasing ever since.

Where all has the chase led the human race now, but longer summers, hotter summers, worse summers. How many more summers can the human race survive through? Only the sun and rising ocean waters know. There is some weird irony in the most sought-after surf-and-sun season now lunging forward, monstrously, in some perverted form to cook or drown the world. We have a lot of strange emotions to look forward to. But maybe on some foundational level I feel like this is always how it was gonna go. It takes me back to childhood. Blazing hot days, the overwhelm of atmosphere, and a yearning for what could have been; so small in a big, burning world, and so vividly alive.

Originally published in Desert Times, August 2023. Written one summer night, July 2023.